Stumbling away from me, hands outstretched mummy-like, a nearly naked man appeared to be walking among the crowd. A group of Asian tourists had gathered around, but the man didn’t flinch. As I drew closer, I smiled with relief at the joke pulled on all of us unsuspecting participants. The man is a life-like sculpture.

Tony Matelli created the Sleepwalker sculptor.

He is known for his lifelike sculptures

The Sleepwalker is part of a public art exhibit called Wanderlust by artist Tony Matelli. The figure is one of several pieces that remind travelers that encounters with nature, art, and architecture are the stuff of everyday life. The painted bronze sculpture immediately shocked me into awareness of my surroundings. For me, it was a perfect introduction to the High Line, a big wake up call to notice the out-of-the-ordinary in the Big Apple.

The sleepwalker sombulates toward the tranquility of the gardens above a noisy street in the Chelsea District. Even though I know he’s not real, a twinge of empathy bubbles up as I might relate to awakening in public wearing only my skivvies and asking Where am I? Nearby, tired wayfarers have kicked off their shoes and splash in the stream of water running over the sidewalk.

We stroll along in a throng of humanity while benches, water features, traffic observation platforms (yes, areas of stadium seating for contemplating the traffic below), people watching, and flowers beckon. The 1.5-mile park stretches from the Meat Packing District (Gansevoort St.) to the 34th Street Hudson Yards.

Ironically, I can’t imagine a more hostile landscape for pedestrians than The Hudson Street Yards. It’s a massive parking lot for trains. In 1934, the tracks carried an elevated freight train rumbling through buildings shaking windows and doors while transporting dairy products from the docks into the city. In 2003, skeptical urban planners ventured into this adaptive reuse project unsure that this was a viable solution for a decommissioned railroad. Thirteen years later, this implausible idea is one of the trendiest redevelopment sites in the city. It’s first iteration was also an unlikely success. It’s hard to believe that while standing in the quiet above a busy intersection we are now lifted out of the world of frantic “getting and spending” that William Wordsworth saw as the cost of modernity in his poem The World is Too Much With Us.

The High Line exposes space between the spaces. The park is a path of well-tended gardens above the streets below. Only the underside of the steel girders are visible from the ground. Two stories above the commercial district, the High Line cuts between the buildings on either side. The park gentrified the space above one of the least desirable areas in the city. Wealthy apartment dwellers now gaze down upon two lower economic stratospheres of the park and the traffic pulsing through intersections below. The park is a Jane Jacobs sidewalk above a Jane Jacobs neighborhood, layered on a bustling historic city grid. It’s living anthropology.

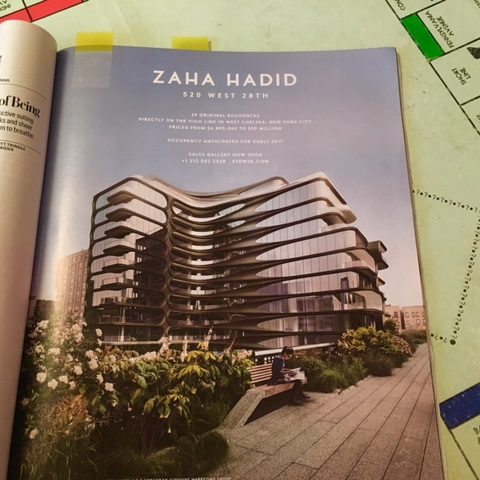

It’s hard for me to fathom paying between $4 to $50 million to live above the High Line.But that’s what people are paying to buy into starchitect Zaha Hadid designed residences on 520 West 28th, Certainly, if you spend that kind of money, a park should come with the deal. The wealthy are the beneficiaries of a fascinating thing happening all along the Eastern Seaboard. A new generation has moved in and is repurposing dilapidated old architecture and infrastructure and making something trendy and desirable. But who was displaced? Were did they go?

The old spur of the New York Central Railroad metamorphosed in two phases between 2006 and 2012. In that six-year span, the many gardens along the park have flourished; young trees defy logic and thrive in the planters between the rails of old tracks. Native plant species, some call them weeds, sprout between the concrete and the rusty steel.

Me and my husband and traveling companion,

Dave, on the High Line.

City dwellers need a respite from the world of “getting and spending”. Color, texture, bees, and gardeners tending the flower beds attract people. So far, commerce is confined to kiosks and venders selling books, T-shirts, and tchotchkes. At the street level, near the Whitney Museum of American Art, a cheerful sandwich shop with orange and blue umbrellas suggests it would be nice to have a coffee under the shade of rusting girders. The nook is a pop-up restaurant made possible by a visionary who saw a bit of crab grass growing between the cracks in the sidewalk and imagined a full blown park.