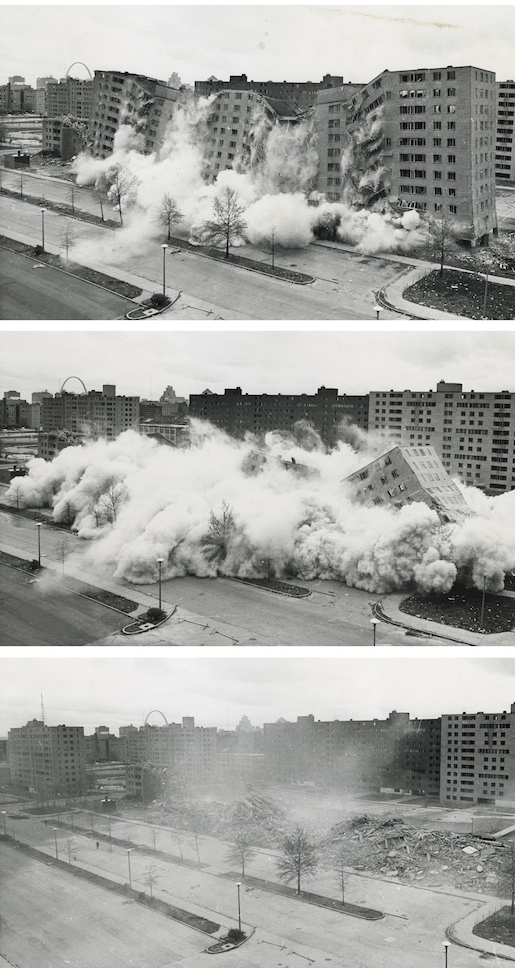

April 1972. The second, widely televised demolition of a Pruitt-Igoe building that followed the March 16 demolition. Photo by U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development

When I was researching Modernist architecture for my Master’s thesis, the name Pruitt-Igoe was often cited as the symbol of the Modernist’s Movement’s greatest failure. Completed in 1956, the architect, Minoru Yamasaki’s government subsidized complex of 33 buildings became the example of everything that was wrong with Urban Renewal.

The Modernist design, some said, encouraged crime in Pruitt-Igoe because rival gangs could easily control the entry and exit points, thus terrorize residents. I discovered that this was only half the story. The movie, the Pruitt-Igoe Myth, an Urban History tells the other half of the story.

Modernist architects were blamed for most of the ills caused by Urban Renewal. But, the story is so much more complicated than that. Pruitt-Igoe was built in the post-WWII age of the automobile and new suburban living. Anyone who could afford to escape the dirty city did. With the aid of Government subsided mortgages, many in the middle class grabbed the opportunity. Furthermore, cars made travel to and from the city cheap and affordable.

In an overview of Minoru Yamasaki’s career for New York Magazine on August 27, 2011, Justin Davidson wrote that Yamasaki’s aesthetic arose from his cultural alienation due to his Japanese heritage. He “was tormented regularly as a child for his ethnic origins.” Further, Yamasaki grew up in a Seattle slum and based on his own experience, he believed that decent affordable housing as the first step out of poverty. He reasoned that having that opportunity should not require poor city dwellers to live in substandard housing.

April 1972. The second, widely televised demolition of a Pruitt-Igoe building that followed the March 16 demolition.

Photos by U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development

Today, massive urban housing complexes are referred to as “the projects.” Many believe it’s only a step above being homeless. But, was the failure of Pruitt-Igoe really all about the architecture? As Pruitt-Igoe Myth points out, a crucial piece of the story is missing. St. Louis abandoned the building and didn’t budget for basic upkeep such as replacing burned out light bulbs in dark hallways. It became a victim of the “Broken Windows Theory.”

St. Louis, was hard hit by the recession of the 1970s. By 1972, Pruitt-Igoe’s reputation was so infamous that the city was anxious to literally wipe it off the face of the earth and did so in a spectacular explosion. Architectural critic Charles Jenks declared, at the exact moment the building came down, on July 15, 1972 at 3:32 p.m.,that that was the end of Modernism.

Even though the buildings now exist only as ghost images, they left a lasting legacy of a particular time, place, and cultural period in St. Louis, MO history. The explosion of Pruitt-Igoe is long gone, but the cultural and racial underpinnings still reverberate today.

As the Michael Brown story puts Ferguson, MO in the news, I wonder, is history reversing itself? Now the trend is for the well-to-do to move back into the city. Is urban gentrification making city living unaffordable for lower income people? Are cities investing in public transportation? Who is left out, especially when spending public money becomes controversial?