In my previous post, I focused on the grounds surrounding Manitoga, Russel Wright’s garden. In this post, I’m taking you inside his house.

Russel Wright (1904-1976) believed so strongly that Americans should find their own cultural identity through architecture that he built an experimental house. He chose a cliff overlooking a granite quarry (later turned into a man-made lake). He saw no reason why Americans should copy European architecture; instead, he challenged us to find our own style. In 1942, Wright purchased 75 acres situated between the Hudson River and the Appalachian Trail in the town of Garrison, and he began building Manitoga, The name pays homage to the native Algonquin people and the word translates loosely as “a place of great spirit.” His American home is hidden among the ferns and moss-covered rocks. One sort of stumbles upon it.

Russel Wright (1904-1976) believed so strongly that Americans should find their own cultural identity through architecture that he built an experimental house. He chose a cliff overlooking a granite quarry (later turned into a man-made lake). He saw no reason why Americans should copy European architecture; instead, he challenged us to find our own style. In 1942, Wright purchased 75 acres situated between the Hudson River and the Appalachian Trail in the town of Garrison, and he began building Manitoga, The name pays homage to the native Algonquin people and the word translates loosely as “a place of great spirit.” His American home is hidden among the ferns and moss-covered rocks. One sort of stumbles upon it.

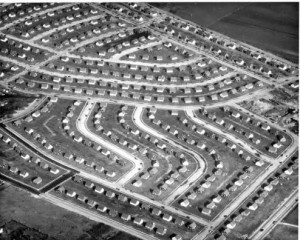

Levittown New York.1949 – Photo from – Levittown Public Library

Manitoga is Wright’s answer to fighting the conformity of Levittown, the suburb built between 1947 and 1951 on Long Island, NY. A flyover image of Levittown is so familiar today that many people automatically conjure Malvina Reynolds’s “Little Boxes” protest song against urban sprawl. There is no way Manitoga could be mass produced.

The cave-like interior of Manitoga snuggles up against the landscape. The setting fits the famously shy Wright. A Princeton trained industrial /theater designer, sculptor, and self taught naturalist, Wright envisioned the dining room table as the heart of the home and put it center stage in his floor plan. Natural light floods the interior and his rooms are divided by fabric, glass walls, and open room dividers. Narrow corridors connect private rooms to public spaces. He paired woven fabrics with aluminum kitchen utensils, and plastic place settings with curvy pottery. Rock walls, a spiral staircase, hidden rooms, and nooks and crannies calm the nerves as if one is walking in the woods. The layout certainly would discourage his daughter Ann from running indoors. While he may not have been sensitive to the needs of all rambunctious children, he had only one child and he consciously designed for her needs. He and Mary, Wright’s wife, designed for the American woman who lived in the era when high school girls took Home Economics. Their contribution was a casual line of pottery named American Made, affordable tableware that became popular in the 1950s and 60s. The organic shaped dishes came in melamine and ceramic; either way, the pieces made an everyday table setting look sophisticated. The settings came in black, pink, turquoise, and white. Wright didn’t leave anything to chance. He experimented until he discovered what color plate best enhanced the natural color of the food on the plate — it was black. Wright’s goal was to be as sensitive in his interior design — right down to plating food — as he was in his landscape design.

His overall theme was blends and contrast. Smooth rocks became doorknobs, flat stones became stairs, butterflies and leaves pressed into glass doors became walls and a natural rock wall encased in floor-to-ceiling glass became a shower that is half inside and half outside. He believed as the seasons changed, so should the interior. In the summer, the table linens and upholstery slipcovers were blue; in the fall, they were switched to orange. Wright planned the furnishing in Ann’s bedroom to be replaced as she matured. Mary died when Ann was only two years old, so Russel gave Ann and her governess a private space. He also designed his studio to be his own private space on the opposite side of the house. The room is below ground-level and offers a “worm’s eye-view” from the window.

His overall theme was blends and contrast. Smooth rocks became doorknobs, flat stones became stairs, butterflies and leaves pressed into glass doors became walls and a natural rock wall encased in floor-to-ceiling glass became a shower that is half inside and half outside. He believed as the seasons changed, so should the interior. In the summer, the table linens and upholstery slipcovers were blue; in the fall, they were switched to orange. Wright planned the furnishing in Ann’s bedroom to be replaced as she matured. Mary died when Ann was only two years old, so Russel gave Ann and her governess a private space. He also designed his studio to be his own private space on the opposite side of the house. The room is below ground-level and offers a “worm’s eye-view” from the window.

In Wright’s house, fireplace screens became kitchen curtains, a honeycomb pattern made of toilet paper tubes encased in plastic make another interesting divider, and canisters are made of shiny aluminum. All stages require dramatic lighting and Wright created a statement chandelier that descends from above via a pulley system. The wheel holds 8 candles and it visually ties the upper floor in Manitoga to the ground floor.

Every part of the house was created as an artistic statement. You might take away ideas, but Wright would say, Don’t copy this house! Build your own!